I hate you, I mentally transmit as I step across the threshold and through the great maw of House.

Past the entrance is a reception area with softly playing

muzak that agitates my senses. This is House’s

first attempt to lull me into security, but I won’t waver. For as long as I must be here, I’ll remain

observant, attentive and vigilant. A

small waiting area contains comfortable chairs and a large mural depicting a

school of rainbow trout. Their

iridescent scales are striking, they are commonly eaten as food. I approach a scowling receptionist and ask directions. She hears me but does not look up from her

work.

‘Ward Five.’ she says.

Drilling my hands into my pockets I proceed down a hallway festooned with directional signage punctuated by obligatory art. More fish. I breeze past the hard-working people who prop up House. Each one is dressed in their appropriate costume, no doubt hard won by years of school. Matching aqua shirts and pants made from harsh fabric and the occasional white coat. I imagine what it must be like to casualise this place – to work here every day. To exist inside this gently undulating organism which dispenses life and death in equal measure.

My thoughts bring me to the dead possum I’d found the other

week. The awful drama of death played

out on my front lawn. I recall with

shame how I’d averted my eyes from his pristine corpse. It was a truth I was still reluctant to

accept. Our bodies fail, and when they

do, they end up here, populating the veins and arteries of this House. Each day, the costumed workers perform their

tasks. Halfway between a butcher shop

and a body shop, they punch a clock at the nexus of fate, time and magic. I hate them and admire them at the same time.

I stare at my shoes as I walk. They are too tight and they squeak in a

manner that annoys me. Sometimes I think

about throwing them into a river, but ultimately, I don’t. I’d only have to buy new ones, which is

always a gamble. I hate to gamble. Proceeding as instructed, I walk through a

pair of automatic doors that bolt open as I approach. Discreetly, I steal glances at the rooms that

branch off from the hallway and catch sight of sleeping people encased in

rough-hewn blankets. Some of them sit

upright in their beds and eat sandwiches, the kind that come in triangular

plastic containers.

I take note of words not used in daily vernacular, at least

not in the circles I’d come to frequent.

Radiology. Oncology. These uncommon words frighten me and conjure

vivid images of sickness and prolonged suffering.

Nice try, I tell

House. You can’t scare me with your ten-dollar words.

I am here to see my friend Petrov who’s undergone surgery to

remove his gallbladder. Poor

Petrov. His short stay inside House had

punctured his uneventful life. Now, he’d

been moved to a different ward. As his

friend, I was here to visit with him during his convalescence because that’s

what decent people do (or so I’m told).

I don’t enjoy my visits with Petrov here. They’re stilted and different from the usual

way we are together. We talk for about

half an hour each time. Post operative,

he sits there in his hospital gown and his underwear, graciously accepting my

halting conversation and pretending to like the magazine I’ve brought him. I don’t know what a gallbladder is exactly,

but I find the very idea of it disgusting.

Sedated and alone, Petrov had been taken into a sterile room where he’d

been opened with a blade, his innards exposed and adjusted like obscene watch

repair.

At fifty-one years of age, the prospect of having to endure

such a procedure is fearful inducement to remain healthy. I do not smoke or drink, take regular exercise

and avoid unnecessary sugars. Such

measures are by no means a guarantee of health, and no insurance against injury

or accident, but I savour the illusion of superiority. As though I can permit myself a certain

modicum of aggrievement should genetics or fate suddenly serve up cancer or a

surprise stomach ulcer. Despite efforts

to conserve my body (begun in earnest in my early twenties), I am tired in a

way only a man of my age could

be. Day by day, I perceive my body

gradually slowing down, succumbing to the twin bitches of gravity and time.

Further into House, more automatic doors reveal more fearful

words against beige and pastel-coloured walls.

The liminal nature of this place stirs the slowly churning anxiety that’s

brewing in my belly. This is how old

people exit the world, quickly replaced with newer, fresher versions that

assume their place. Admittedly, death is

not always the outcome of an internment here – undisputed marvels of modernity had

shrunk mortal injuries into routine outpatient procedures. One could visit and leave many times during a

lifetime – until one didn’t. My own

parents had endured the same process, one followed closely by the other. No matter how beneficent it seems, the House always

wins. Sooner or later, it summons and

digests us all.

I’ll die by the side

of the road before I let you take me, I curse under my breath.

Still seeking Petrov, I pass beds containing small bodies,

most of them ancient, looking so reduced, cocooned in blankets atop adjustable

beds. Men and women in their seventies,

eighties and nineties, the scaffolding of themselves incrementally collapsing

under the combined stresses of a life well lived, or at least, well

played.

It’s at this moment, in my periphery, that I see a face I

thought impossible. A face so familiar,

I freeze. Not caring that I am

obstructing the doorway to an old man’s room, I gawk at him, slack jawed and

disbelieving. He is much older than I

remember, but I do remember. Vividly and with frequency, his countenance

visits me in daydreams when I am low.

When I consider my early childhood a sad and solitary affair, his memory

begs to differ. Every line, every

contour and imperfection still present, but distorted, his face affected by the

decades like wind upon sand dunes. It is

the face of The Man who was my friend when I had none. I never thought I would see his like again,

let alone here, in the bowels of this creature, being digested himself.

***

I wait in the kitchen for The Man to arrive like he always

does after Mum and Dad leave for work. Work

means they go away in the morning and come home when I am sleeping. I sit on top of the kitchen table and swing

my legs over the edge. Mum always tells

me off when she sees me, but she’s not here to see it.

Nana is in her bedroom, watching her stories. She tells me not to bother her. I know she doesn’t care about me, but I don’t

mind. I have my own games I play, and I

have The Man. He lives behind the

fridge. Only I can see him. He says it’s better that way. That adults only cause problems. So I keep him secret.

‘What do you do all day by yourself?’, Mum would ask sometimes.

‘Nothing.’ I’d reply.

I know it’s bad to keep secrets, but if I told them, Mum and

Dad would only start yelling. I hate it

when they yell.

The Man is fully grown, and much taller than I am. He steps out from behind the fridge wearing a

black suit and a tie. He looks very

fancy, like he is dressed up special, but he is always that way. His hair is black and shiny and he always has

a cigar.

‘Not till you’re fifteen.’ he tells me when I ask if I can

try it.

That’s ten years away.

Ten years is forever. I wonder if

I will wear a suit when I’m fifteen? I

don’t know his name, so I just call him The Man.

The Man and I spend our days playing in the house, running

through the big corridor being aeroplanes and sometimes trains. I sit high upon the The Man’s shoulders and

pretend that I’m a crane. I’m never

scared when I’m with The Man – I know he’d never let me fall. Sometimes we are noisy and Nana comes out to

yell at me. I like noises, and I wonder

why they’re bad. It scares me when she

yells, but then she stops and I can go back to being an aeroplane. Nana is very old and her hands are very

wrinkly. Dad says she’s just bitter.

I like The Man more than Dad. Dad is always tired when I ask him to

play. He comes home late and sits by

himself. I only ever see Dad at night. I never get a good look at his face, but I

think it is sad. The Man is different. He is funny and clever and I like to ask him

all kinds of questions. Sometimes the

questions are small, other times they are big ones that I think about at

night.

‘What is time?’ I ask The Man.

‘Nobody really knows.’ he says, ‘But you only get so much of

it.’

In the living room, The Man and I do drawings in crayon and

colour pencil. Once I ate six crayons

and had to go to the doctor. I ask The

Man what work is. He says that grown-ups

have to go away sometimes, but it doesn’t mean they don’t love you. The Man goes away every day, back to behind

the fridge. He says goodbye and shakes

my hand. The Man treats me like I am a

grown up.

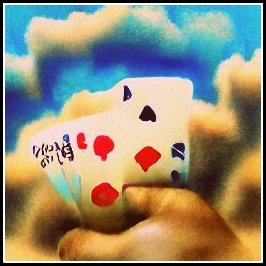

When it’s raining and we can’t go outside The Man and I play

board games. The Man likes to play games

with Nana’s cards. One day, he tells me

he’ll teach me a card game that grown-ups play.

I bet my set of coloured pencils, twenty cents and a train from my train

set. The Man warns me not to get greedy.

‘The house always wins.’ he says.

The man has to go away – but he promises he will see me

again, sometime in the future.

‘What is the future?’, I ask.

‘The future’s just like the past, only with the lights on.’

‘Will I be there?’

‘Sure you will, but you won’t recognise yourself.’

***

He was a physical impossibility, an absurd living artefact

of a thing I’d since discarded in the wastebin of my mind. A makeshift big brother, surrogate father,

conjured by the nascent psyche of a lonely child. No matter.

My feelings were real – still simmering warm and bright through the fog

of the many decades that separated that moment and this.

As I stare at him, discreetly enquiring after my own sanity,

I attempt to apply reason to the situation.

The Man would have been my age when I was a kid, but this poor soul

looked a great deal older. Even so, the

resemblance was uncanny, the same slicked back hair (now white) unperturbed by

the rumpled pillow. I move towards his

bed to view his chart. Coronary artery

atherosclerosis – loathsome words so jagged I cannot form them in my

mouth. I check for his name: John Doe.

The Man opens his eyes and sees me, so he extends his

hand. I sit with him, beside his bed,

Petrov be damned (he could wait). I

speak to him, but I’m not sure he can hear me.

Nearby, a bouquet of devices makes their presence known with a symphony

of rhythmic trilling and beeping. A

nurse appears in the doorway, words of admonishment already in her mouth, but

she sees me, holding The Man’s hand and hesitates. Her eyes soften, and her face marked by

overwork is awash with understanding.

Quietly, she floats away and goes about her business.

The Man’s eyes are dull and milky and his hand is spotted

and ugly with age and bony with protrusions.

My father looked this way just before he’d left us, his path cut short by

drink and a deep, abiding sorrow.

Strange that I should conjure him now, in the presence of this stranger,

his ample shadow casting ably from the grave.

As I hold the man, I can feel the embers of his flame growing dull. I stay with him, determined not to let him to

be digested all alone in this charnel house.

I ponder how from a certain perspective, the present time

can always be regarded as “the future”.

It is a distant, unwritten shore as far away from us as adulthood is to

a child. I consider this notion as I

recall The Man’s promise, now fulfilled, as I soak in the exquisite symmetry of

the moment. Here we both were, together,

just like he’d prophesised. I decide

then and there the veracity of his identity is immaterial. He, or at least the ghost of him, had been

there for me when I needed him.

Returning the favour was the least I could do.